Why Japanese is officially the world's toughest language. Part I: language isolate with multiple layers of vocabulary.

There is literally no idiom in the universe that is harder to learn

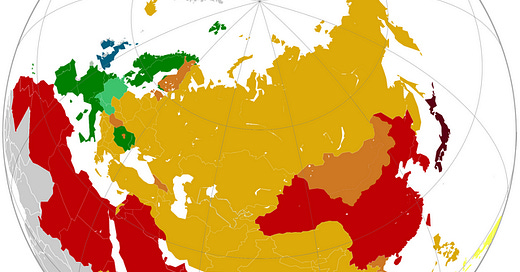

Many many moons ago last century, in a sleeping compartment of a night train, I had a heated discussion with an Arabic interpreter. He claimed that Arabic is the toughest language ever, whilst Japanese is “just a bunch of characters with readings”. At the time, I could not counter his argument with any data as the Internet was in its fragile infancy, and googling on your mobile was not even a sparkle in Sergey Brin’s eye. A couple of decades later, I came across the infographic above and finally felt vindicated.

So this is official. Japanese is the toughest language on Earth ever (for native English speakers anyway). In the map above, it stands out in foreboding dark maroon, a notch above even the notoriously hard to crack Chinese and Arabic. It takes at least four times as much time, effort, sweat and tears to get your Japanese to a functional level than Spanish — which is not an easy language, have you seen the verb conjugation tables?

In reality, those 88+++ weeks can be stretched out much further. And it’s 88+++ weeks, if you have 25 hours of professional face-to-face instruction and half a day of daily homework non-stop each and every week. If you can’t abide such intensity and prefer to take it easy and study just one hour every week (yet without ever taking a break), that’ll take you 49 years, thank you very much. And, if we are honest enough, you need to be quite linguistically gifted or even that won’t be happening.

All that just to get you to an intermediate level. Solid intermediate, which means you will be able to just about make a living using Japanese as the medium of communication at work. However, you still won’t manage to read a newspaper or engage in a deeper conversation on grownup topics such as politics or economy. Your vocabulary will be limited and everything else too will be just about middle-of-the-road, nothing outstanding. Yeah, I know! Phew.

Do you want to learn Japanese in fun-packed and efficient individual lessons?

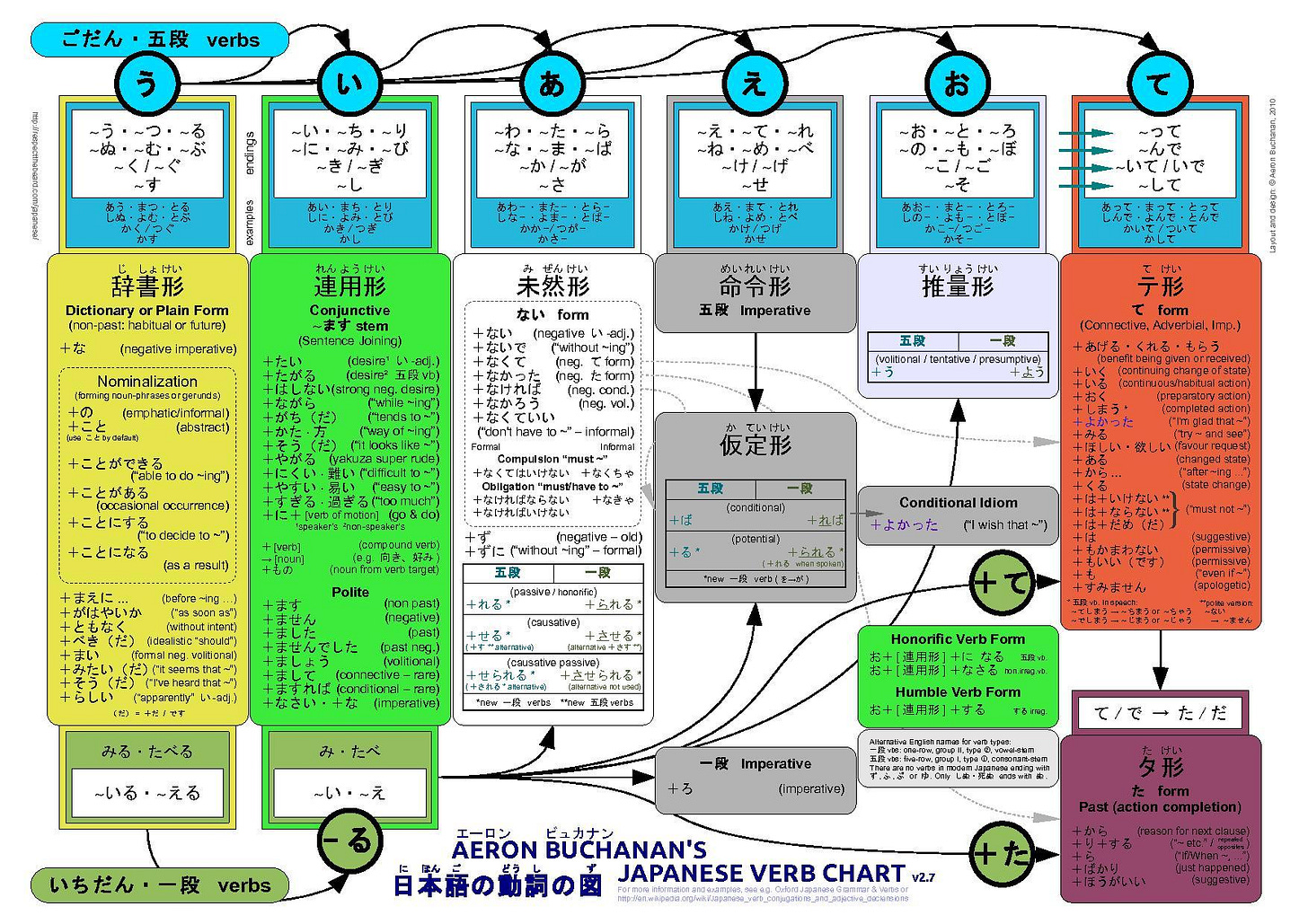

That is, actually, really peculiar. Japanese should be much easier to master. Grammatically, it is very streamlined and harmonious. It doesn’t have three completely random grammatical genders like in German or Russian, or 15 grammatical cases like in Finnish or Hungarian, or three grammatical numbers like in Slovenian or Lithuanian. There are no multiple declensions for adjectives or numbers like in Russian or Polish. And there are literally just two exceptions in the whole verb conjugation table, unlike in Romance languages where verbs are literally made of irregularities. There are only two tenses, past and non-past, as opposed to 26 in English, and no first, second, or third person for verbs. All Japanese verb conjugations can be fitted into one largish table.

The English verb to be conjugates like this:

I am we are

(thou art) you are

he/she/it is they areThe Japanese verb to be (である) conjugates like this for every person in Present Tense plus Future Tense (shall be/will be):

desu (です)

Japanese phonetics are as harmonious and mellifluous as in Italian: consonant, vowel, consonant, vowel, consonant, vowel. No baffling tones like in Chinese, Thai, or Vietnamese. No 21 vowels like in Korean, just five. No complex classes of consonants like in Indic languages (that I still can’t make the head or tail of). Japanese sounds can be mastered in 20 minutes. So what happened? How has Japanese ended up all the way at the top of the difficulty charts? Why does it take four times more effort to learn than Romanian or Swedish? Well, there are a few things going on there.

Firstly, Japanese is a language isolate: it has no confirmed linguistic relatives. That means that native Japanese words are not related to any known language — except for Ryukyuan languages and the Hachijō language (that you probably have never heard of). For a (non-Asian) learner of Japanese that means that there will be practically nothing familiar in terms of vocabulary. For example, there is a fair degree of similarity among the basic vocabularies of the Indo-European languages of Europe (and grammar too but that’s another huge topic). Japanese words, on the other hand, are completely out of this world. Mother is moeder in Dutch, Mutter in German, madre in Spanish, mere in French. In Japanese that’s haha or okāsan. The Sun is zon (Dutch), Sonne (German), sole (Spanish), solntse (Russian). In Japan the daylight comes from hi, taiyō, or o-tentō-sama (Japanese synonyms are numerous!). One in Dutch is een, ein in German, uno in Spanish, un/e in French. In Japanese it’s hitotsu.

With native Japanese, Old Chinese, and recent English layers of vocabulary Japanese is one of the few world’s languages developed enough to write either a novel, or a instruction manual how to build a space rocket, or a PhD thesis.

‘No!’ I hear you protest. One in Japanese is ichi. Yes, but that’s not a native Japanese word. Over half of Japanese active vocabulary ultimately hails from (various varieties) Old Chinese, just the way most European languages draw on Latin and Ancient Greek for elevated and technical vocabulary. E.g., revolution is revolutie, revoluccion, or something similar and very easy to guess across most of Europe. In Japanese it’s kakumei. Police (politie, Polizei, polizia, policija, etc.) is keisatsu. Airport (aeroporte, auerpuerto, etc.) is kūkō. That means that the whole vocabulary needs to be learnt from scratch. There is practically no shared frame of reference. Granted, there is a large number of borrowings from English but they are tweaked, twisted, and naturalised, sometimes to the point of irrecognisability. For example:

pasokon is a contraction from pasonaru kompyūtaa, ‘personal computer’

remokon is, predictably, remōto kontororu ‘remote control’

rorikon, however, is not ‘rolling ball control’ but Rorita kompurekkusu ‘Lolita complex’, that is, your common-or-garden ‘nonce’. Would you ever guess that?

The Japanese also do a great job inventing English words that don’t even exist in English (和声英語 wasei-Eigo). When rendered directly back into English, this kind of lingo makes absolutely no sense:

ハンドルキーパーはバックミラーにソープランドを見た。

Handorukīpā wa bakku mirā ni sōpurando wo mita.

“The handle-keeper saw a soap-land in his back mirror.”

You won’t make sense of this sentence without a glossary:

handorukīpā ("handle-keeper") = ‘designated driver’

bakku mirā (“back mirror”) = ‘rear view mirror’

sōpurando (“soap-land”) = ‘brothel’

You fink me done? Me just a-come! There is soooo much more. I already wrote how even simple counting in Japanese requires a degree in advanced countology. Next week I will touch on how making up a decent Japanese sentence is akin to making multiple back-flip somersaults on a tightrope while balancing a china set on the tip of your nose. Let me know your thoughts about what I wrote above in the comments below.

If you feel affected by the issues described above, please share your concerns, comments, corrections, sarcastic jabs, or righteous indignation below.

Well, this has made me feel much better about my progress... It feels tough to learn - because it IS tough! I do love the language though.